What's a CURIE, and Why You Should be Using Them

Compact uniform resource identifiers, or CURIEs, are an important formalism for referencing biomedical entities. This post explains what they are, how to write them yourself, and a brief outline of how they fit in to the semantic web, linked open data, and open biomedical ontology worlds.

In the semantic web, linked open data, and ontology communities, uniform resource identifiers (URIs) are used to reference named entities. For a given nomenclature, like the Chemical Entities of Biological Interest (ChEBI), URIs usually have two parts:

- A URI prefix (in red)

- A unique local identifier from the given nomenclature (in orange)

All the URIs from the same nomenclature will have the same URI prefix, but a different unique local identifier. Here’s an example, using the ChEBI unique local identifier for alsterpaullone:

https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chebi/searchId.do?chebiId=138488

The Trouble with URIs

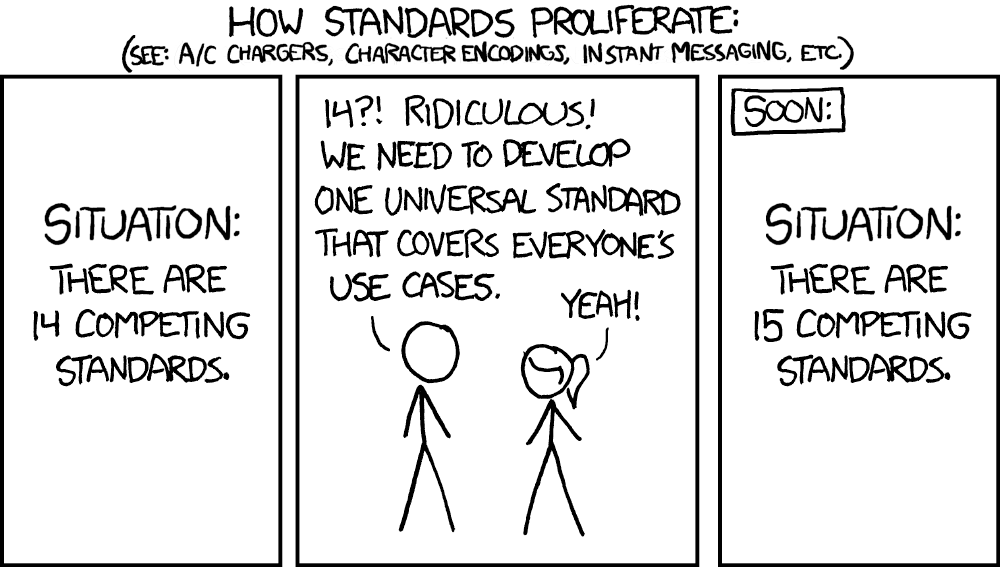

URIs are inconvenient because each named entity could be referenced by

potentially many URIs. For example, a URI could start with either http or

https. Even worse, there are several competing services that each try to mint

the one true URI for each. XKCD sums the ensuing chaos up pretty well:

For the example molecule, alsterpaullone, here are some (but not all) of the possible URIs that could be used to reference it:

| Provider | URI |

|---|---|

| First-party | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chebi/searchId.do?chebiId=138488 |

| Identifiers.org | https://identifiers.org/CHEBI:138488 https://identifiers.org/CHEBI/138488 http://identifiers.org/CHEBI:138488 http://identifiers.org/CHEBI/138488 |

| OBO Library PURL | http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/CHEBI_138488 |

| Name-to-Thing | https://n2t.net/chebi:138488 |

The real issue with URIs is that the URI prefix (the beginning part) doesn’t really tell you anything. In fact, given a URI, you usually have to do some detective work to figure out which nomenclature authority it goes with.

One solution was to use resolvers that create “persistent URLs”, but in the end, there are many competing resolvers that don’t cover everything. For example, the OBO PURL system doesn’t cover HGNC and UniProt. The Identifiers.org system doesn’t cover many ontologies.

For practical purposes, it makes sense to keep track of the commonly used names of each resource, then just generate the kinds of URIs that people might want depending on what software or data systems they’re working with rather than prescribing one URI to be the canonical one.

Come to the Dark Side, We have CURIEs

The solution is to use compact uniform resource identifiers (CURIEs), which replace the URI prefix with a more approachable prefix. A CURIE has three parts:

- A prefix (in red)

- A delimiter (in black)

- A unique local identifier from the given nomenclature (in orange)

Since everyone agrees on what ChEBI is, it makes sense to use chebi as the

prefix for ChEBI unique local identifiers. Here’s the same example for

alsterpaullone, condensed as a CURIE:

chebi:138488

The best part of a CURIE is that you can associate your favorite URI prefix with its corresponding prefix depending on your use case. You can even have a database that stores all of the possible ones for you. Replacing URIs with prefixes is so common, that it’s a core part of the SPARQL query language, which is used both in the semantic web and ontologies to traverse data stored in the resource description framework (RDF) schema. Here’s an example SPARQL query that has these prefixes prominently at the top:

prefix obo: <http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/>

prefix owl: <http://www.w3.org/2002/07/owl#>

prefix rdfs: <http://www.w3.org/2000/01/rdf-schema#>

prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#>

SELECT ?x ?p ?y

WHERE {

{?x rdfs:subClassOf [

a owl:Restriction ;

owl:onProperty ?p ;

owl:someValuesFrom ?y ]

}

UNION {

?x rdfs:subClassOf ?y .

BIND(rdfs:subClassOf AS ?p)

}

?x a owl:Class .

?y a owl:Class .

}

This example was borrowed from the SPARQL queries in the repository for the

Core Ontology for Biology and Biomedicine (COB).

You don’t have to understand the SPARQL itself, just check the first 4 lines

that start with prefix ....

How to Build a CURIE

Most common vocabularies can be written as CURIEs. Here are a few examples:

| Name | Prefix | Example Unique Local Identifier | Example CURIE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Ontology | go | 0032571 | go:0032571 |

| HGNC | hgnc | 16793 | hgnc:16793 |

| UniProt | uniprot | P0DP23 | uniprot:P0DP23 |

| Disease Ontology | doid | 0110974 | doid:0110974 |

| Medical Subject Headings | mesh | C063233 | mesh:C063233 |

As you might guess, most prefixes are either the acronym for a nomenclature

authority or the name itself. There are a few cases where this isn’t true, like

for Disease Ontology. Their acronym is DO, but then that add ID which is usually

shorthand for “identifier”, and therefore get doid as a prefix.

Just to reiterate, it’s really easy to make a CURIE. You take the prefix, a colon, then the unique local identifier and smash them together! Note: some communities, like the Open Biomedical Ontologies Foundry, like to stylize prefixes with uppercase or mixed-case. If you live in URI world, this is a big deal, but for most practical purposes, it’s nice to be able to just keep it all lowercase.

How do you know what’s the right prefix for each resource? And who even keeps track of this stuff? The Bioregistry keeps an up-to-date list that you can browse or search here. My team at Harvard Medical School has been building this with help from the community to serve the community needs that previous registries didn’t - most importantly, to make the data open and transparent and to enable community suggestions in an open and fair way.