Challenges with Semantic Mappings

There are many challenges associated with the curation, publication, acquisition, and usage of semantic mappings. This post examines their philosophical, technical, and practical implications, highlights existing solutions, and describes opportunities for next steps for the community of curators, semantic engineers, software developers, and data scientists who make and use semantic mappings.

Proliferation of Formats

The first challenge with semantic mappings is the variety of forms they can take. This both includes different data models and serializations of those models. This problem is effectively solved, but I think is worth reviewing for historical purposes (please let me know if I missed something):

![]() Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS)

is a data model for RDF to represent controlled vocabularies, taxonomies,

dictionaries, thesauri, and other semantic artifacts. It defines several

semantic mapping predicates including for broad matches, narrow matches, close

matches, related matches, and exact matches.

Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS)

is a data model for RDF to represent controlled vocabularies, taxonomies,

dictionaries, thesauri, and other semantic artifacts. It defines several

semantic mapping predicates including for broad matches, narrow matches, close

matches, related matches, and exact matches.

JSKOS (JSON for Knowledge Organization Systems), a JSON-based extension of the SKOS data model. I recently wrote a post about converting between SSSOM and JSKOS.

Web Ontology Language (OWL) is primarily

used for ontologies. It has first-class language support for encoding

equivalences between classes, properties, or individuals. Other semantic

mappings can be encoded as annotation properties on classes, properties, or

individuals, e.g., using SKOS predicates.

Web Ontology Language (OWL) is primarily

used for ontologies. It has first-class language support for encoding

equivalences between classes, properties, or individuals. Other semantic

mappings can be encoded as annotation properties on classes, properties, or

individuals, e.g., using SKOS predicates.

The

OBO Flat File Format

is a simplified version of OWL with macros most useful for curating biomedical

ontologies. It has the same abilities as OWL, but also the

The

OBO Flat File Format

is a simplified version of OWL with macros most useful for curating biomedical

ontologies. It has the same abilities as OWL, but also the xref macro which

corresponds to oboInOwl:hasDbXref relations, which are by nature imprecise and

therefore used in a variety of ways.

The

Simple Standard for Sharing Ontological Mappings (SSSOM)

is a fit-for-purpose format for semantic mappings between classes, properties,

or individuals. SSSOM guides curators towards inputting key metadata that are

typically missing from other formalisms and is gaining wider community adoption.

Importantly, SSSOM integrates into ontology curation workflows, especially for

Ontology Development Kit (ODK)

users.

The Expressive and Declarative Ontology Alignment Language (EDOAL) lives in a similar space to SSSOM, but IMO was much less approachable (c.f. XML + Java), and has not seen a lot of traction in the biomedical space.

OntoPortal has its own data model for semantic

mappings that has low metadata precision. I recently wrote a post on converting

OntoPortal to SSSOM. OntoPortal would also like

to invest more in SSSOM infrastructure if it can organize funding and human resources.

OntoPortal has its own data model for semantic

mappings that has low metadata precision. I recently wrote a post on converting

OntoPortal to SSSOM. OntoPortal would also like

to invest more in SSSOM infrastructure if it can organize funding and human resources.

Wikidata has its own data model for semantic

mappings that include higher precision metadata. I recently wrote a post on

mapping between the data models from SSSOM and

Wikidata.

Finally, there’s a long tail of mappings that live in poorly annotated CSV, TSV, Excel, and other formats. Similarly, mappings can live in plain RDF files, e.g., encoded with SKOS predicates, but without high precision metadata.

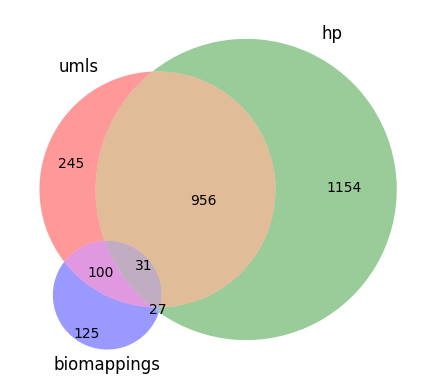

Scattered, Partially Overlapping, and Incomplete

Semantic mappings are not centralized, meaning that multiple sources of semantic mappings often need to be integrated to map between two semantic spaces. Even then, these integrated mappings are often incomplete. Using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and the Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) as an example, we can see the following:

- MeSH doesn’t maintain any mappings to HPO.

- HPO maintains some mappings as primary mappings.

- The Unified Medical Language System (UMLS) maintains some mappings as secondary mappings. HPO suggests using UMLS as a supplementary mapping resource.

- Biomappings maintains some community-curated mappings as secondary mappings.

This actually might not be the best example - it would have been better to show a pair of resources that both partially map to the other. When I first made this chart, I had to engineer the UMLS inference by hand. Eventually, the need to generalize this workflow led to the development of the Semantic Mapping Reasoner and Assembler (SeMRA) Python package which does this automatically and at scale. The fact that there were missing mappings that even UMLS inference couldn’t retrieve led to establishing the Biomappings project for prediction and semi-automated curation of semantic mappings. The underlying technology stack from Biomappings eventually got spun out to SSSOM Curator and is now fully domain-agnostic.

Different Precision or Conflicts

Another challenge with semantic mappings is when different resources have

different level of precision. In the example below, OrphaNet uses low-precision

mapping predicates (i.e., oboInOwl:hasDbXref) while MONDO uses high-precision

mapping predicates (i.e., skos:exactMatch). It makes sense to take the highest

quality mapping in this situation, but having a coherent software stack to do

this at scale was the big challenge (solved by SeMRA).

This can get a bit dicier when there might be conflicting information, for example, if one resource says exact match and another says broader match. In SeMRA, I devised a confidence assessment scheme (which should get its own post later).

Common Conflations

There are three flavors of conflations that make curating and reviewing mappings difficult that I want to highlight.

Different Ontology Encodings

Classes, instances, and properties are mutually exclusive by design. This means that any semantic mappings between them are nonsense, but there are many situations where these mappings might get produced by an automated system or by a curator who is less knowledgable about the ontology aspect of semantic mappings. There’s also a much more subtle discussion about classes, instances, and metaclasses ( see this discussion) that I would set aside.

As a concrete example, the

Information Artifact Ontology (IAO) has a

class that represents the section of a document that contains its abstract:

abstract (IAO:0000315). Schema.org

has an annotation property whose range is a creative work and whose domain is

the text of the abstract itself: schema:abstract.

These both have the same label abstract, which means that it’s possible to

conflate (i.e., accidentally map them).

Different Entity Types

The second kind of conflation is even more subtle, when two classes, instances, or properties come from similar but distinct hierarchies.

For example, there’s a subtle difference between what is a phenotype and what is a disease. Ontologies are highly apt at encoding this subtlety with axioms that can then be used by reasoners. This can become a problem for curating and reviewing semantic mappings because some diseases are named after the phenotype that it presents or that causes it. Using MeSH’s disease hierarchy and HPO’s phenotype hierarchy as an example, we can see that Staghorn Calculi (mesh:D000069856) and Staghorn calculus (HP:0033591) should not get mapped.

Many more examples can be produced (which also show there are even more

subtleties here) using SSSOM Curator with the command:

sssom_curator predict lexical doid hp. See the

SSSOM Curator documentation

for more information on the lexical matching workflow.

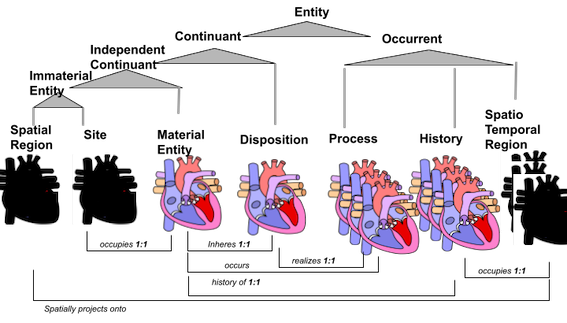

Different Senses

The basic formal ontology (BFO) is an upper-level ontology that is used by many ontologies, including almost the entire Open Biomedical Ontologies (OBO) Foundry. However, as Chris Mungall described in his blog post, Shadow Concepts Considered Harmful, there are many different senses in which an entity can be described, each falling under a different, mutually exclusive branch of BFO. The figure below, from Chris’s post, represents different senses in which a human heart can be described:

This problem is particularly bad in disease modeling. Here are only a few examples (of many more) that illustrate this:

- the Ontology for General Medical Science (OGMS) term for disease (OGMS:0000031), the Experimental Factor Ontology (EFO) term for disease (EFO:0000408), Monarch Disease Ontology (MONDO) term for disease (MONDO:0000001) is a disposition (BFO:0000016)

- the Gender, Sex, and Sexual Orientation Ontology (GSSO) term for disease (GSSO:000486) is a process (BFO:0000015)

- the Human Disease Ontology (DOID) informally mentions that a disease is a disposition, but doesn’t make an ontological commitment to BFO

- many more controlled vocabularies including NCIT, SNOMED-CT, and MI have their own terms for diseases but don’t use BFO as an upper-level ontology nor are constructed in a way conducive towards integration with other ontologies

Schultz et al. (2011) proposed a way to formalize the connections between the various senses for diseases in Scalable representations of diseases in biomedical ontologies. However, the OBO community has yet to resolve the long and taxing discussion on how to standardize disease modeling practices.

For semantic mappings, this becomes a problem because a reasoner will explode if diseases under two different BFO branches get marked as equivalent, because the BFO upper level terms are marked as disjoint - this is a feature, not a bug. However, while useful for creating carefully constructed, logically (self-)consistent descriptions of diseases, these modeling choices can be confusing when curating or reviewing mappings. These modeling choices might not be so important in downstream applications, such as assembling a knowledge graph to support graph machine learning, where many different knowledge sources with lower levels of accuracy and precision must be merged. In practice, I have merged triples using conflicting senses for diseases in a useful way, without issue.

Interpretation is Important

While the last few examples were cautionary tales for when things (probably) shouldn’t be mapped, the next examples are about when things (probably) should be mapped.

Definitions

Here are three vocabularies’ terms for proteins and their textual definitions (though, many more contain their own term for proteins):

| Entity | Label | Description |

|---|---|---|

| wikidata:Q8054 | protein | biomolecule or biomolecule complex largely consisting of chains of amino acid residues |

| SIO:010043 | protein | A protein is an organic polymer that is composed of one or more linear polymers of amino acids. |

| PR:000000001 | protein | An amino acid chain that is canonically produced de novo by ribosome-mediated translation of a genetically-encoded mRNA, and any derivatives thereof. |

As semantic mapping curator, we have two options:

- We can reasonably assume that the intent from all three resources was to represent the same thing, despite the definitions being quite different. This assumption can be built on our prior knowledge about what a protein is, why Wikidata, SIO, and PR exist, and then infer the intent of the term’s definition’s author

- We can make a very literal reading of the definition and conclude that these three terms represent very different things

I think that the latter is really unconstructive for several reasons, but I have worked with colleagues, especially from the linguistics background, who take this approach. First, this is unconstructive because it means you’ll probably never map anything.

Second, if you want to be rigorous, use an ontology formalism with proper logical definitions. For example, the Cell Ontology (CL) exhaustively defines its cells using appropriate logical axioms. However, this also has a caveat, that to make mappings based on logical definitions, then the different modelers have to agree on the same axioms and same modeling paradigm. As far as I know, there aren’t any groups out there that use the same modeling paradigm that haven’t just combine forces to work on the same resource. So we’re stuck back at option 1 either way :)

Context Sometimes Matters

In contrast to the discussion about mapping phenotypes and diseases, there are context-dependent reasons to make semantic mappings, which can be illustrated in biomedicine using genes and proteins. Let’s start with some definitions:

- SO:0000704 A gene is a region of a chromosome that encodes a transcript

- PR:000000001 A protein is a chain of amino acids

The biomedical literature often uses gene symbols to discuss the proteins they encode. While this isn’t precise, it’s still useful in many cases. Therefore, when reading the COVID-19 literature, you will likely see discussion of the IL6-STAT cascade, where IL6 is the HGNC gene symbol for the Interleukin 6 protein. Most of the time, the HGNC approved gene symbol is an initialism or other abbreviation of the protein, but this isn’t always the case.

Edit: Sue Bello pointed out that most journals enforce gene names being put in italics (IL6) and proteins without italics, though this requires the author and reader to know that distinction, as well as for formatting to be preserved, which it often isn’t unless you’re reading the original PDF or publisher’s HTML.

Similar to the literature, many pathway databases that accumulate knowledge about the processes and reactions in which proteins take part actually use gene symbols (or other gene identifiers) to curate proteins.

The take-home message here is that genes and proteins are indeed not the same thing, but in some contexts, it’s useful to map between them. There’s also a compromise - the Relation Ontology (RO) has a predicate has gene product (RO:0002205) that explicitly models the relationship between IL6 and Interleukin 6, which can then be automatically inferred to mean a less precise mapping for certain scenarios (SeMRA implements this).

Outside of biomedicine, I have also heard that context-specific mappings are very important in the digital humanities. As I’m better understanding the use cases of colleagues in other NFDI Consortia that focus on the digital humanities, I will try and update this section to have alternate perspectives.

Evidence

A key challenge that motivated the development of SSSOM as a standard was to associate high-quality metadata with semantic mappings, such as the reason the mapping was produced (e.g., manual curation, lexical matching, structural matching), who produced it (e.g., a person, algorithm, agent), when, how, and more.

We developed the Semantic Mapping Vocabulary (semapv) to encode different kinds of evidence such as for manual curation of mappings, lexical matching, structural matching, and others. SSSOM is well-suited towards capturing simple evidences (blue).

Provenance for Inferences

The purple evidence from the figure in the last section requires a more detailed data model to represent provenance for inferred semantic mappings that simply doesn’t fit in the SSSOM paradigm (and it shouldn’t be hacked in, either). I proposed a more detailed data model for capturing how inference is done in Assembly and reasoning over semantic mappings at scale for biomedical data integration and provided a reference implementation in the Semantic Reasoning Mapper and Reasoner (SeMRA) Python software package. Here’s what that data model looks like, which also has a Neo4j counterpart:

Negative Semantic Mappings

SSSOM also has first-class support for encoding negative relationships, meaning that the following can be represented:

This means that SSSOM curators can keep track of non-trivial negative mappings, e.g., when curating the results of semantic mapping prediction or automated inference. In a semi-automated curation loop, this allows us to avoid re-reviewing zombie mappings over and over again.

High quality, non-trivial negative mappings also enable more accurate machine learning, as opposed to using negative sampling. For example, we have been working on developing graph machine learning-based ontology matching and merging using PyKEEN (a graph machine learning package I helped develop and maintain).

An open challenge is that we neither have support from data modeling formalisms (e.g., ontologies in OWL, knowledge graphs in RDF or Neo4j) to encode negative knowledge (in this case negative mappings) nor tooling support. This means that when we output SSSOM to RDF, we use our own formalism, which won’t be correctly recognized by any other tooling that wasn’t developed with SSSOM in mind. I’m keeping notes about this in a separate post about negative knowledge that I update periodically.

Despite the challenges, I think that the mapping world is actually getting quite mature. I am currently working with NFDI and RDA colleagues to further unify the SSSOM and JSKOS worlds, especially given that the Cocoda mapping curation tool solved many of these problems (from the digital humanities perspective) many years ago, and we simply were unaware of it.

I hope this post can continue as a living document - if I missed something, please let me know and I will update the post to include it!